Photo: Justin Bastien

Do you want to run faster? Longer? I’ve compiled the 5 best ways to do just that. Runners often find themselves at a plateau, seeing minimal-to-no progress over time, failing to improve their 5k, 10k, or marathon year after year.

Especially adult recreational runners that never ran competitively in high school or college typically don’t have much knowledge of training to improve performance. This is the majority of the running population. If you want to

continue to improve your running, regardless of experience or age, keep on reading.

What determines running ability in the first place? Let’s start by talking about nature vs. nurture. For explanation purposes, let’s break down all runners into four categories based on their genetic gifts and ability to be nurtured

into better runners:

- Higher baseline with high training response

- These runners are genetically gifted with respect to their baseline running performance and their ability to improve their running quickly with training. With training and proper focus, these athletes become elites and

Olympians.

- These runners are genetically gifted with respect to their baseline running performance and their ability to improve their running quickly with training. With training and proper focus, these athletes become elites and

- Higher baseline with low training response

- These runners are genetically gifted with respect to their baseline running performance, but may not improve very much with training. These athletes have to work harder to achieve the same progress as Group 1, but still

have the potential to be high-level runners. In rare scenarios, these athletes may even have elite-potential at baseline.

- These runners are genetically gifted with respect to their baseline running performance, but may not improve very much with training. These athletes have to work harder to achieve the same progress as Group 1, but still

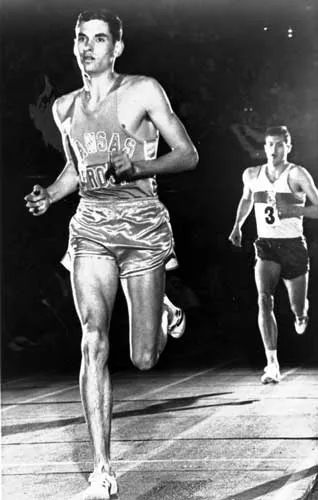

- Lower baseline with high training response

- These runners have average to low baseline running performance but respond very effectively to training, making them able to improve significantly over time. A small percentage of these runners also have the potential to

become high-level runners, but with more training over time.- Example: As a result of high training response and high-intensity training, Jim Ryun became the first high schooler to run a sub-4 min mile after not even making the “B team” during his early high school years.

- These runners have average to low baseline running performance but respond very effectively to training, making them able to improve significantly over time. A small percentage of these runners also have the potential to

- Lower baseline with low training response

- These runners have a low starting point for their running fitness and don’t respond very well to training. These runners can train very hard with minimal improvement and are unlikely to become elites or Olympians.

You might already have an idea of what group you fall into, or maybe not. Unless you’re already a gifted runner, most of us should start by putting ourselves in Group 3. If we train smart, we should see an improvement of some kind,

and the amplitude of which may give us a more accurate idea of our training potential. I believe that we should all consider the possibility of being the next Jim Ryun until proven otherwise.

Run More

This is easily the most obvious answer and most commonly attempted way to improve running. Simply running more can be very effective at improving cardiopulmonary fitness but can also lead to injury or overreaching (overtraining) if

done incorrectly. If you’ve never tried to run more miles per week, that’s by far the most straightforward way to improve your running. Start by increasing your mileage by no more than 10% per week with a “recovery week” every 4-6

weeks. So if you’re consistently training at 25 miles per week, try running 27-28 miles the next week, then 30 the week after that. Keep in mind that if you’re running trails with a lot of vertical ascent, that factors into your

overall training load. In this case, try the same rule but use “ weekly time on feet” instead of weekly mileage.

Train Smarter

Most runners head out for their run, without a specific pace in mind, and often end up running a similar pace each time they run. Even on “tempo” days, runners aren’t running fast enough. In general, most runners run too slow on

their “fast days” and too fast on their “slow days”. Speed-work should truly challenge you. And conversely, rest-days should be very slow and almost relaxing. In general, challenging the body with planned rest thrown in there is the

most beneficial. Keeping the body thinking and adapting is the best way to improve.

Strengthening

A common misconception is that strength training for runners will increase muscle size and ultimately be a detriment to running because of the added bulk and weight. But studies have shown that this is not true for runners.

Strengthening has shown to improve running economy, reduce/delay fatigue, improve anaerobic capacity, and reduce risk for injury. Runners are typically very weak and can get very sore after their first strength training session. So

take it easy. The intensity of soreness will be less after subsequent sessions. Start with body-weight exercises like squats, lunges, planks, and bridges, then don’t be afraid to progress to using barbells, dumbbells, and

kettlebells. Looking for some help getting started with strength training? I’m putting together a FREE starter-kit for runners. Click here to learn more.

Plyometrics

Plyometric training or “plyos” are jumping or bounding exercises that utilize the elastic properties of muscle to increase muscle performance. Training the elastic component of muscles can be greatly beneficial to a runner’s economy

and performance. Plyometric training develops neural and muscular elasticity to generate maximal force in the shortest amount of time. Given this, plyometrics are often used as a method of training to bridge the division between

strength and speed. Doing plyos once or twice a week is a good start since it can be easy to do “too much too soon” if you jump straight into it.

Here are some great exercises to start with.

Preventing Injuries

Ultimately, preventing injuries will allow consistent training without interruption. 75% of runners get some sort of injury every year. If you can keep yourself out of that statistic, you’ll see more running improvement through

continuous training. The majority of running injuries can be attributed to “training errors”. This means, running too much before your ready, or diving too aggressively into speed work or plyometrics. Another large portion of

injuries can be attributed to weaknesses or muscle imbalances which relates to the importance of the last two tips, strengthening and plyometric training. For example, Runner’s knee (kneecap pain) and IT band syndrome are both

strongly correlated with weakness in the hips, according to the research. So strengthening is part of injury prevention as well as performance improvement.

Bonus and Conclusion: Periodization

Periodization refers to strategically planning training throughout the year in order to complement and maximize training effects. This can be a very complicated topic but I recommend simply carrying over the concept of “planned

training”. Using the above-mentioned tips, I encourage you to focus on organizing your training so that you can benefit the most from each. For example, increasing your mileage at the same time as getting into strengthening can be

counter-intuitive. I encourage you to find someone to coach you through your training to maximize your training. I often help my clients with developing a training plan, but if you’re looking for a specialized running coach, I

recommend Jennifer Fishman with F3 Coaching and

Nate Grimm with Endurance Matters Coaching.